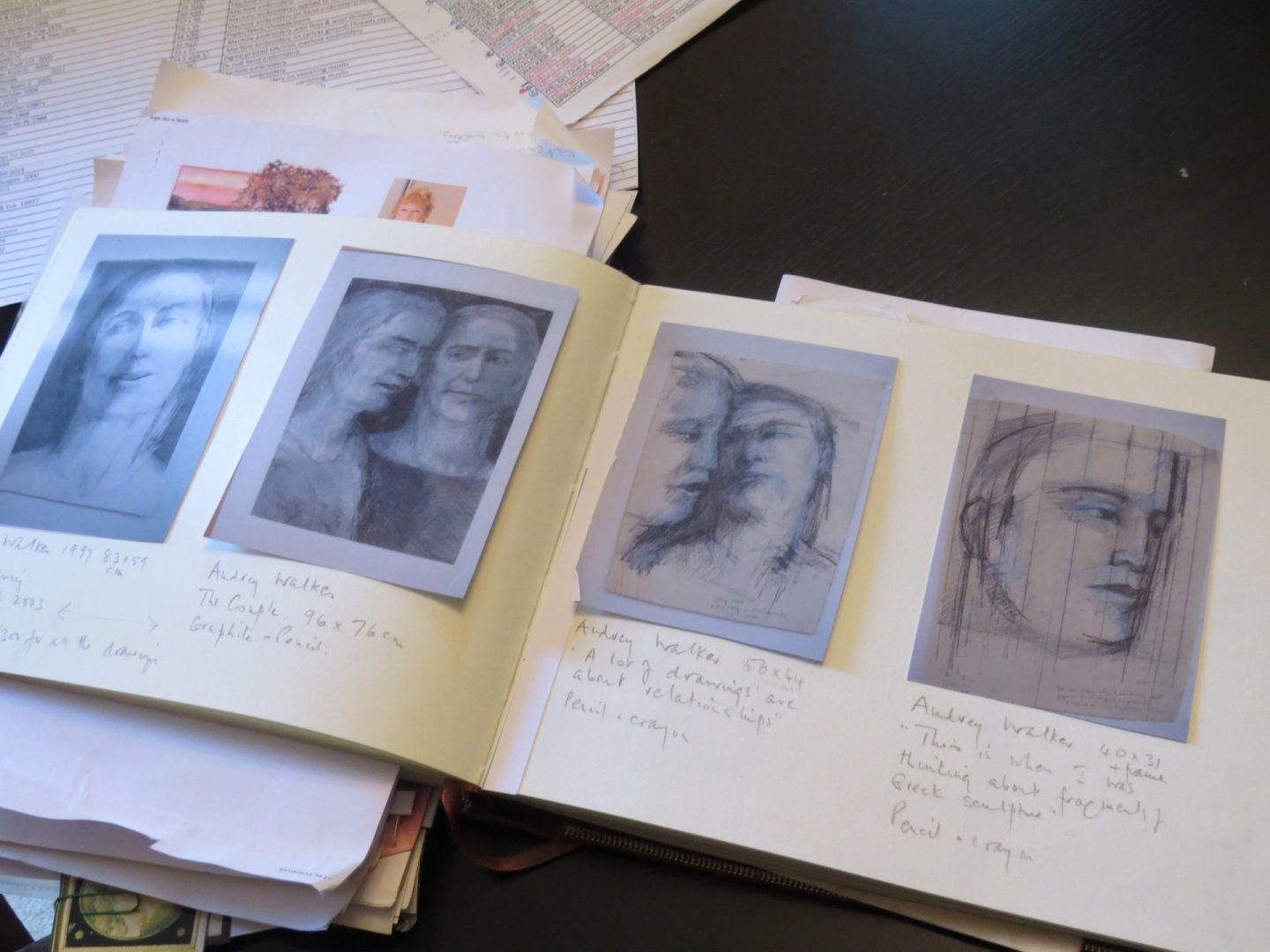

Artists she has championed and whose work you will find in her private collection include Alice Kettle, Jean Littlejohn, Audrey Walker and Karen Nicol.

Springall’s own work is held by the Victoria & Albert Museum as well as the Embroiderers’ Guild and to date, she has authored five books on the subject of embroidery. She is a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a former chairman of the Embroiderers Guild and the Society of Designer craftsmen.

However, the artist’s life was not a lifestyle choice Springall’s parents expected of their daughter. Born 1938 in Shimla, the summer capital of British ruled India, Springall grew up rarely seeing her parents, instead of living under the charge of her nanny. She and her brother began smoking to fit in before being caught when plumes of smoke rising from the herbaceous borders. She hasn’t smoked since but has instead, and much to her parents’ consternation, picked up another bohemian vice; a passion for art.

After fleeing India on a troopship when British rule came to an end in 1947 the family relocated to Britain and Springall was sent to boarding school for her first taste of formal education. She attended three schools; Edinburgh then Hastings, before settling at Hawkhurst.

Springall joined Goldsmiths in what could be considered the golden age of Textile art.

In 1954 The University placed the subject of Embroidery on a par with Painting, Sculpture and Illustration.

Gaining equal status as an art form made it a more academic, respectable subject and made it easier for students like Springall, who arrived in 1956 to incorporate textiles into their work without appearing quaint or crafty.

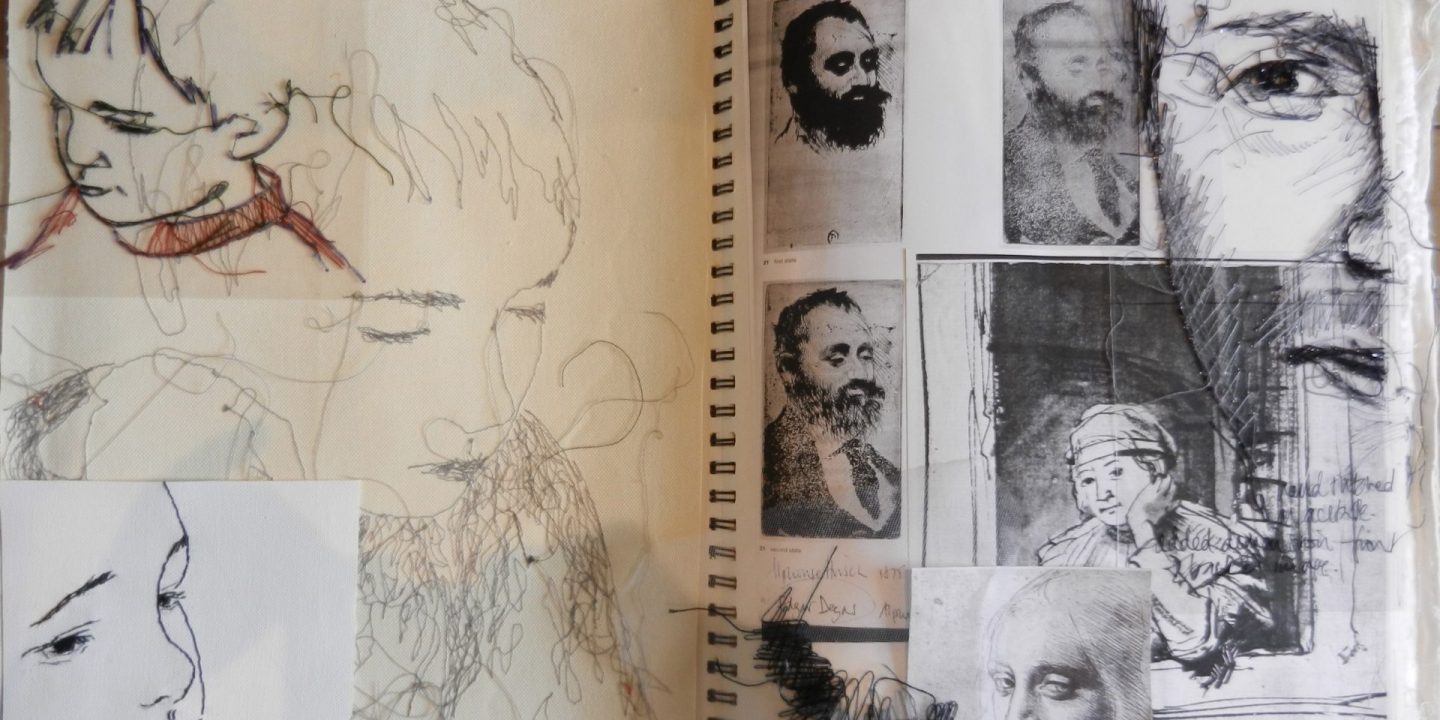

Springall was at Goldsmiths to study painting but took evening classes with artist, writer and teacher Constance Parker. Describing Parker, Springall calls her ‘very much the Queen Bee’ and paints a picture of a dominant course leader, highly critical of students work and a major force in reshaping the perception of embroidery at that time. Springall who is also often described as an ‘artist-writer-teacher’ says the comparisons end there.

"She and her brother began smoking to fit in before being caught when plumes of smoke rising from the herbaceous borders."

Whereas Parkers’ regime would involve total adherence to strict rules Springall is more relaxed. Also, Parker herself was not as prolific an artists as Springall; in that sense, very few people even come close.

Despite the upheaval and radical gear changes Springall thrived at Hawkhurst and learned to be self-reliant and independent. Her father who had been in the senior ranks of the Indian civil service expected his daughter would aspire to be a nurse or a secretary.

When she expressed an interest in doing an extra year to complete her Art A-Level and put together her portfolio for Art School he was reluctant and suggested ‘he wasn’t at all sure about spending another year to educate me, he‘s already wasted the other years, I was clearly not bright’.

Springall explains that her mother who could embroider but couldn’t boil an egg held a similar view. Between them, they believed the pursuit of art could only lead to a life of ‘poverty and sin’.

Perhaps the colonial upbringing coupled with a boarding school education inspired the rebel in Springall. Against her parents’ desires, she pushed on and was offered a place studying fine art at Goldsmiths. The deal brokered with her parents and essential at that time was that Springall would go on to study to qualify as a teacher ‘just in case’.

Karen Nicol, the leading contemporary textile and embroidery artist and winner of the 2015 Beryl Dean Award said of Springall’s work, ‘Diana brings an artist’s eye and informed sophistication to embroidery that is very special and transcends time and fashions in the craft. She is a true artist/designer who uses textiles as her medium, not allowing the process to dictate and inhibit the work of art’. This high praise from one artist to another demonstrates the significant contribution Springall has made and continues to make.

In recent years Springall has continued to produce work but concedes she is less inclined to use a step ladder than she once was.

She delivers popular talks on the subject of Textile art and artists and has been a mentor and judge in the Hand & Lock Prize for Embroidery. Her experience as chairman of the Embroiderers Guild guarantees she has a strong informed opinion on the ongoing state of British embroidery.

Much of Springall’s time is now taken up in pursuit of the creation of a permanent home for the Textile Arts she holds so dear. A prodigious letter writer, she has written to all the major British museums encouraging, cajoling and pressing them to exhibit textile arts and treat the art form as they would any other art form.

The ultimate goal is for a venue to exist here in London where visitors can see textile arts through the ages and where modern textile artists can exhibit their work. The boxed up works held by the likes of the V&A can finally see the light of day and be celebrated.

Diana Springall gave up smoking when she was five but shows no signs of giving up her artistic endeavours. As an artist, a teacher and an ambassador for the Textile Art community she is second to none.